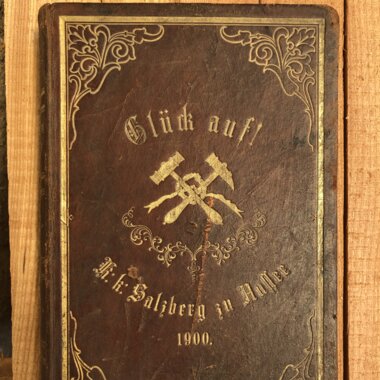

Rediscovered Guestbook A Piece of History Resurfaces in Altaussee

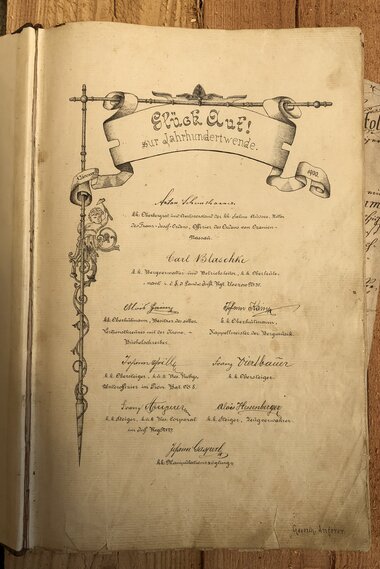

Until now, we had assumed that spur-of-the moment visits to the salt mine in Altaussee had only been possible since the 1920s. Prior to that, you needed to obtain special permission from the salt mine authorities (known as the Salzamt) or the operations manager at the mine itself. Getting permission was not ever a problem, but it did take significantly more effort than visits do today. However, with the discovery of this visitor logbook, we now know that guests have been able to simply stop by since at least 1900.

Guided tours at that time were organized a little differently than todays. Whereas modern guests are shown the subterranean world by specially trained guides, back then the task was assigned to a mine forman, known as a Steiger. Not all the foremen were thrilled to guiding visitors through the mines, so having a grumpy guide was a possibility. Other guides, however, viewed tours as a pleasant change of pace from their usual work routine, and the tips they received were a welcome supplement to their income.

The route of the tour was also a bit different: St. Barbara’s Chapel (“Barbarakapelle”) wasn’t built until 1935 and guests would have had to slide down the infamous “Gegele Schurf”. This slide was so steep that the guide had to use a pair of ropes as a safety brake for his group. From the lower level of the mine, known as the Franzberg horizon, guests would then enjoy a comfortable railway ride out of the mountain in mine carts. However, things were considerably less comfortable for two of the workers: After every tour, it was their job to drag those carts roughly 600 meters back inside the mine without any motorized assistance.

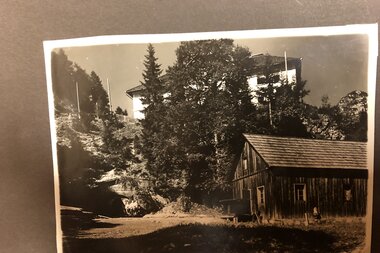

Today, the entrance to the Ferdinandberg gallery has fallen completely silent. In its current state, one would hardly guess that thousands of visitors once emerged here from deep within the mountain. Be that as it may, anyone exploring the Via Salis should definitely pay this historical mine entrance a visit. Only 50 meters from the main trail, the Ferdinandberg mine entrance now also has an info board showing a group of visitors coming out of the mine.

Just as today, visitors in the past also wanted souvenirs of their excursions, so each group was photographed in front of the Steinberg House. Unfortunately, the date and year are not always legible, making precise dating and identification difficult.

In fact, in the late 1980s, an order was issued to clean out the office once used by the mine cartographer and burn all the “trash”. Many documents were simply tossed out of the first-floor window and burned. Kurt Freller, a mine-maintenance foreman, happened to be walking by and his gaze fell upon this particular book. He thought it would be a shame to destroy it, so he took it with him for safekeeping. For many years, it simply lay in his office at home.

But times change. And on one beautiful summer’s day, he handed it over to a Salzwelten employee with the comment: “You’re interested in this old stuff, right?”. As it turned out, I was that employee. I now look forward to inspecting it much more closely and I have no doubt it will have a surprise or two in store for me. Hopefully, I’ll have time to delve into this historical piece this winter when things quiet down a bit. After I’ve learned all I can from this book, it will be turned over to Thomas Nussbaumer as an addition to the new Saltworks Library in Bad Ischl, where it will be made available to others for research purposes.

TO BE CONTINUED…